Anthony Economos solves problems with technology. The 34-year-old husband and father of four serves as the Director of IT for Censis, where he oversees research and development associated with hardware design and applies his problem-solving skills in additional entrepreneurial endeavors.

To say he wears a lot of hats would be an understatement.

“People ask me what I do, and I never know what to say,” Economos said in a recent interview. The way he sees it: “Everything I touch, everything that I do, I hope makes a difference.”

Last year, a Facebook post spurred Economos’ problem-solving mind into action. An 11-year-old boy nearby, born with only partial hands—half palms, no fingers—wanted 3-D–printed hands for Christmas. Economos thought he could figure out how to build them.

Here’s how he tells the story:

Censis: Tell us about Gavin Sumner and how you found out about his Christmas wish for 3-D–printed hands.

Economos: Gavin was born with one foot, so he’s missing a leg, and both of his hands are missing, and then he’s missing like 40 percent of his tongue. … The Facebook post [which had Gavin’s request for hands] was shared with me, and I simply said, ‘Hey, this is something that I think we can solve.’ … I knew I could solve it one way or the other. I just thought it would be easier than it was. [laughs] I bit off more than I could chew at the time.

What made the project challenging?

You think about the hand … you think about the geometry that goes with being able to actually pick stuff up with actual grip force. There are a lot of complex movements going on when you use the function of just picking up a water bottle. You just don’t think about it—I didn’t.

How did you start figuring out how to build Gavin’s hands?

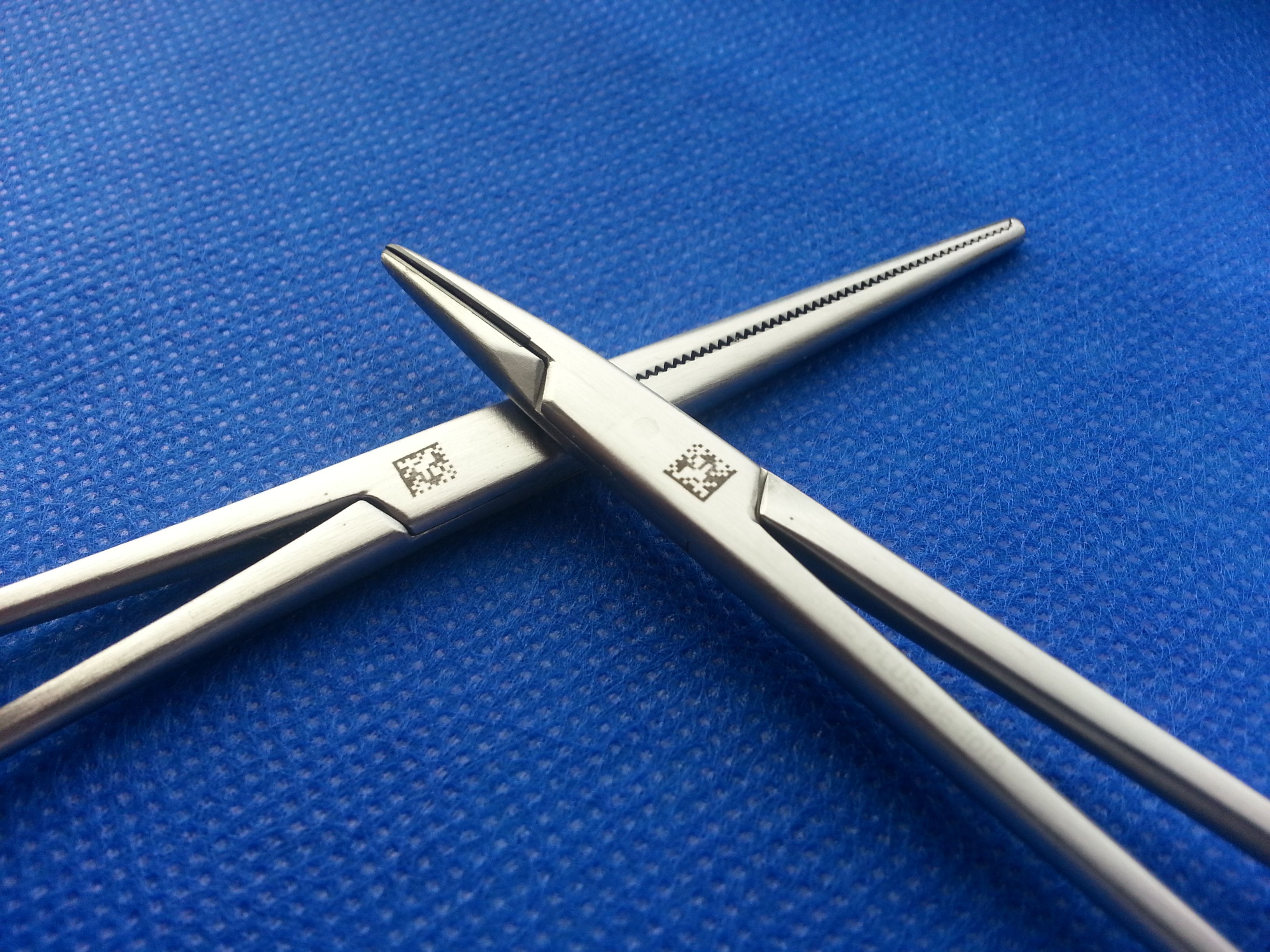

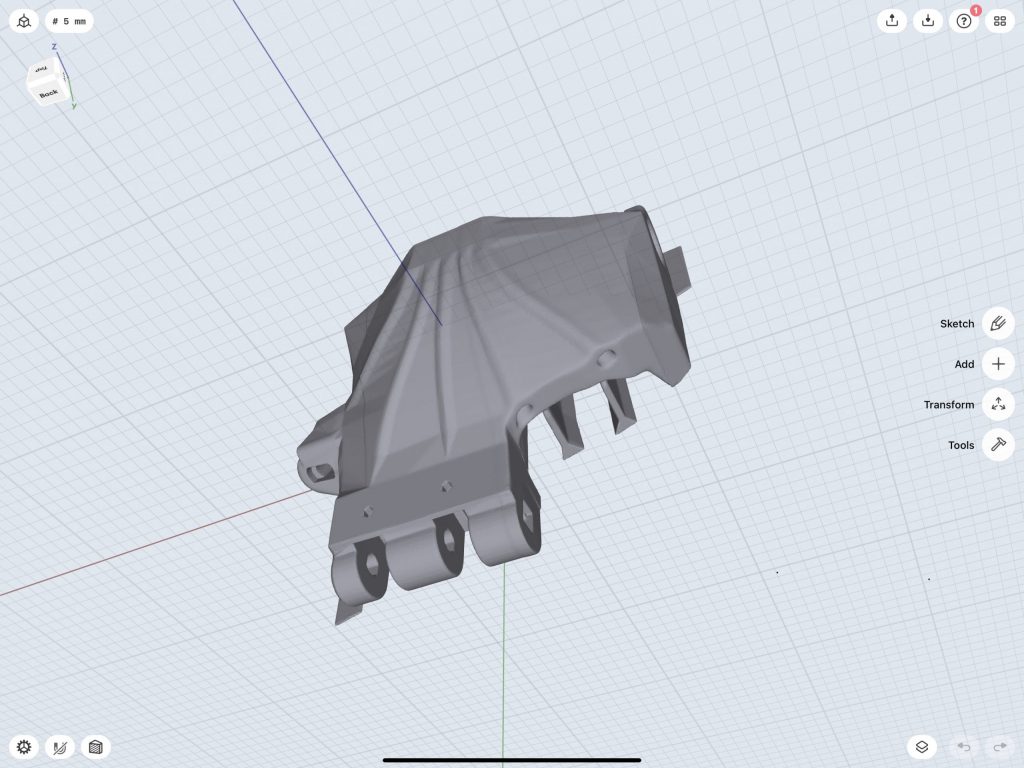

There’s a big community called the e-NABLE Foundation who starts off with a lot of these designs, so you can get a prebuilt hand or a template for the CAD files—but those don’t work out of the box for everybody. You have to modify it. … We modified it because Gavin still has little nubs on his actual palms that prevented the [original 3-D–printed] hands from working as intended.

You didn’t figure out that you needed to make those modifications until after you showed the first prototype to Gavin. How did you make sure the prototype was the right size?

We asked the parent to send us an image that was effectively two feet away from Gavin’s hand with a ruler [that] gives us the ability to import [the image] at scale. So we can pull that picture into a 3-D modeling program and then make sure that we resize the actual CAD file to fit his hand. … The first iteration, our sizing was, honestly, pretty close to perfect before we ever even met him, just from using a photograph.

So Gavin got to try on the first prototype and see if it worked. What happened next?

What we realized is that … he uses the nubs more than we ever anticipated and they protrude further than we expected, so the prototype that we had didn’t work. … [His hands are] diagonally shaped, which just made it really hard to get uniform leverage inside the palm to actuate the wrist [which is how the fingers on the 3-D hand are activated]. … That took us basically back to the drawing board. We went back to the Enable Foundation, presented the use case, but nobody really knew how to solve the problem. After months of thought and multiple iterations, we were able to solve the problem with the help of the volunteer community.

Building the working hands was almost a year-long process, right?

It was, and there were probably six different prototypes, numerous, numerous iterations of trying to find the correct way. Because the problem is that the hands are articulated by wrist movement. When he goes to pick something up, he has to be able to use his wrist, and there were just too many obstacles that were preventing the geometry from working correctly.

It was challenging to figure out how to make the engineering work with Gavin’s wrists, but you also had a specific design in mind that you wanted to stick to.

We wanted to try and keep all five fingers [on the 3-D–printed hand], but the clear answer was to remove fingers from the design. It wasn’t something that I really wanted to do. … We wanted him to feel like he’s normal—and he really was! The kid taught me more than anything I could ever teach him.

The unfortunate side of it was, all those months were kind of wasted because I was not able to keep the fingers as I intended. … In the end, we were able to remove [two fingers from each hand], keep the thumb where it needed to be—because a hand without a thumb doesn’t work. And we were able to get the functionality of the grip working correctly.

How did you actually make the prototypes?

We would 3-D print; we would thermoform. … In some of the original designs, we would boil the polymers in water and then thermoform them over shapes to try and help get the shape that we needed. … The final design, we didn’t do that. We actually printed it with the shapes that we needed, and then we used a leather bottom section so that it had better comfort.

How much did Gavin know about the project?

We didn’t want to disclose too much. We wanted to be as vague as possible because after the first time, where I thought I had it solved … the disappointment when he had to leave without the hand was too great for me. For the longest time, I struggled because … one, I didn’t know how to solve the problem and, two, I just didn’t want to get his hopes up. …

I communicated with his mom directly and got all the information I needed. … There was no way that she could not disclose that something was going on by taking pictures, so I think he knew that there was something going on, but he didn’t know to the full extent. When we actually showed him the hands for the first time, even though they didn’t work, you could sense that he could see there was an opportunity—it was going to get solved. But at that point, we went off the radar and just spoke to mom directly.

When we actually unveiled the hands in December, he didn’t know that they were ready. He had no idea.

Why did he think he was at the Montgomery County Mayor’s Office?

He thought he was there because … his aunt was getting an award from the mayor. And if I was in the crowd, he would have known, so I was actually in the other room. … [The mayor] calls Gavin up … and says, ‘Hey, we have a gift for you.’ He opens it.

What was that moment like for you?

It was really rewarding for me. … This kid who’s met adversity his whole life [and is] just super optimistic, super positive. … I can’t put into words how proud I am to have been able to meet Gavin, and for me, as a father, to be able to show my kids how important it is to use our talents to help others, I’m just profoundly happy.

Since then, the story about you and Gavin and Gavin’s hands has been picked up by news outlets all over—and you’ve started a website called ClarksvilleHelps.com. Tell me about that.

The outpouring of requests for assistance was just huge from more people that needed help … so that’s what we’re working on now: how do we solve problems for others that have other needs, where we use technology and engineering to solve problems for people with disabilities.

What do you hope people take away from your story?

I want to stress how important it is … when you can take your skillset and apply that to a need that other people can use, how rewarding it is, and how much more productive it makes you in everything else you do. The big takeaway for me is to get out, get up, and help. Use your abilities to help another organization. If you’re an engineer, use engineering. If you’re in finance and accounting, there are tons of nonprofits that need help. Use your abilities to help further community projects. That’s really the answer for me.